This is the first part of a three-part series on Gender ngesiZulu, which is something I’ve recently been researching for two different friends.

This is an ancient or ur-Bantu root meaning ‘bed’. It’s very different from the word u(lu)cansi, meaning ‘sleeping mat’ or (euphemistically) ‘sex’. There are no cognates of -lili meaning ‘bed’ specifically.

This root is used in only two of the noun classes – the abstract (ubu-) and the constructed (isi-/izi-). Firstly, and perhaps most easily, have a look at ubu-lili:

Sex, Sex Gender

ubulili besifazane (female gender)

ubulili besilisa (male gender)

The two examples give a clue about isiZulu’s inherent dualism – there are two genders, in much the same way as French or English or others. The ubu- class is ideal for representing this idea, because that’s what it’s for – ideas, essences, abstracts. But, as with almost all the ubu- nouns, there is something concrete from which it is distilled – in this case, isi-lili. Have a look at this one:

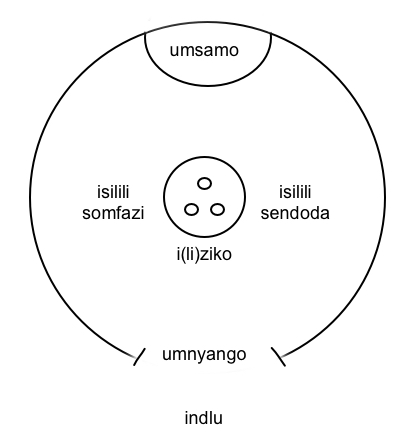

The sleeping place on the floor of the hut

1. isilili somfazi

left-hand side of the hut, where the woman sleeps;

feminine grammatical gender

2. isilili sendoda

right-hand side of the hut, where the man sleeps;

masculine grammatical gender

So, if you’ve never seen an abstract representation of a hut, allow me to show you:

Each gender would have equal access to three key places in the hut or indlu – the door (umnyango), the hearth (iziko) and the sacred place (umsamo).

Take a closer look at the second parts of those two examples – umfazi and indoda, starting with umfazi:

- a married woman or wife (NB: do not use this word to denote ‘a woman’)

- a term of endearment or admiration for a little girl who is particularly good at domestic work

- a term of insult for a loose woman

Well, that escalated quickly. Maybe you’re thinking ‘Perhaps it’s not just with umfazi, let’s have a look at indoda first before making up our minds’. Here you go:

- an adult male person, a man.

- a husband (when used with possessive or in context with a woman)

- an able person of either sex; a manly person. (contrast with i(li)nina)

So the word umfazi tends toward the negative, whereas the word indoda contains only positive and somehow goes beyond describing those who are biologically male.

In order to take a closer look at the understanding of a man, let’s look at the other words using the same isiqu of the word – uku-doda, ubu-doda and isi-doda.

uku-doda

- be a man, act the man, do the work of a man

- do the man’s work for someone

ubu-doda

- manliness

- semen (a euphemism for amalotha)

isi-doda

- male sexual organs (a euphemism for umthondo and amasende

- semen

So basically men are sexually defined, in a definition that links to a gendered division of labour (more on this in part 2).

Looking at words that modify the isiqu slightly, things get very interesting:

in-dodana (lit. little-man)

- son

- son-in-law

in-dodakazi (lit. female-little-man)

- daughter

- daughter-in-law

So children are associated with the male, even to the extent of feminising a diminutive of the word for man in order to create a word for daughter.

There are similar derivations from um-fazi, and this is where our quest leads us now:

ubu-fazi

womanhood; the state of being a married woman

isi-fazana / isi-fazane

- woman-folk (a collective term)

- the pronominal form owesifazane (a human of the women-folk) is the usual term for woman

u(lu)-fazazane

poor sort of women (a collective term)

um-fazazana

- a contemptible or common woman

- the praise name of ingungumbane, the porcupine.

Glancing at these four words shows that there is a high degree of insult associated with the words derived from umfazi – and sadly this is not where it ends (a comprehensive discussion of insults and other derogatory words that are gender-specific is still to come).

There are some equivalents with other words from indoda, including:

in-dojeyana

insignificant man, contemptible man.

u(lu)-dojeyana

group of worthless fellows, contemptible villagers.

But in the end, there does not seem to be the edge to these words that there is for the feminine words.

But why is there no equivalent for isifazane for the words derived from indoda? Why is there no isidodana or isidojana? This question is answered by the use of a separate root entirely, -lisa, in the form

isi-lisa

- male kind, men-folk (collective term)

- the pronominal form owesilisa (a human of the men-folk) is the most neutral word for man

- semen

um-lisa

- male, male person

- able man, daring man

So, once more, the words for male are associated not only with semen, but also with positive qualities. It is quite clear that, even at this most basic level of understanding, gender ngesiZulu is a contested concept that weighs in heavily in favour of the male.

In the next part of this series of gender, I will be looking at different words for humans in terms of gender roles and actions.

3 replies on “Gender pt 1: -lili & the basics”

[…] post is the second part in a series on gender or ubulili ngesiZulu. Please read the first part if you’re lost at any […]

LikeLike

[…] you haven’t already done so, have a look at Gender Part 1 and Part 2, where I discuss some of the other aspects of Gender in more […]

LikeLike

My view on the part of children being associated with the man is such so that the mn must always bare the responsibility of all his children mishaps or not. They are to be raised and taken care of by him. Ee know that naturally a woman would never leave her children uncared for. Adversely weknow that men are more inclined to leave his children. So naming his children after him is to protect his children from being fatherless and making sure that the man takes responsibility. As for the women umfazi being so negative. I believe that this is global. It doesn’t justify it but it is the product of a patriarchal society.

LikeLike